The Comforters

I’m a reasonably fast reader but it has taken me a while to read Volume 1 of Muriel Spark’s Letters. To be fair it took Edinburgh-born academic Dan Gunn six years to reconstruct her life from 1944 to 1963 through her correspondence, and that was after spending 25 years doing similar work on Samuel Beckett’s archive of letters. My sacrifice during these first cold weeks of 2026 has been nothing compared to his and - as I wrote last week - it has been a joy.

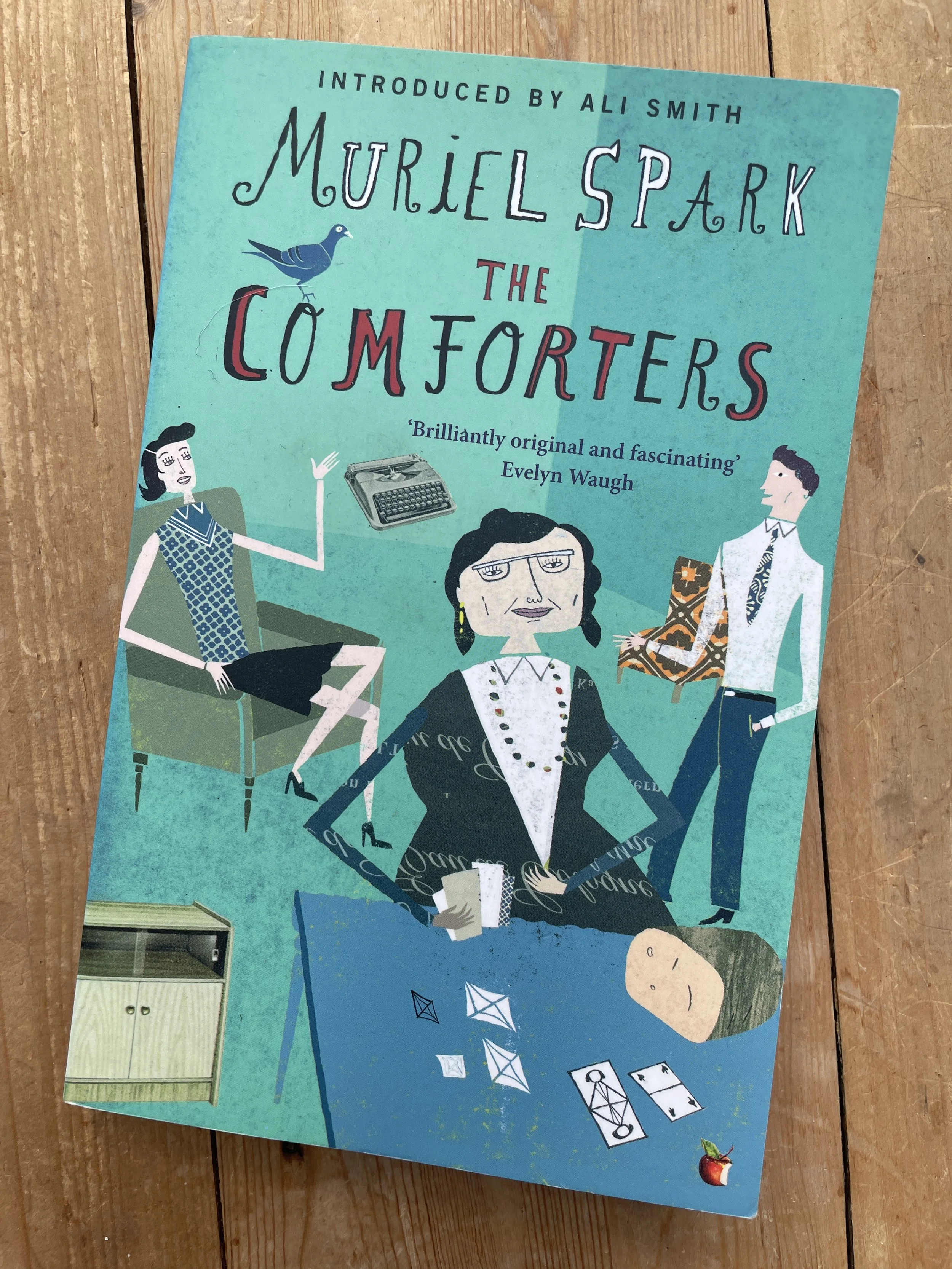

So much so, it has inspired me to return to Spark’s debut novel, The Comforters, written by her 70 years ago and published to much acclaim in 1957.

When I first read it, I cannot now recall. However, the copy I currently have - with its hand-cut paper illustration by Berlin based artist Martin Haake - I note from the receipt, I bought in late March 2017 from the Oxfam bookshop where I now volunteer, although that’s not important. I was, as they say, in a bad place in March 2017, something that happily changed only a few months later. That’s not important either - although at the time - it was for me.

Having now read the Letters, it strikes me that so much of The Comforters is autobiographical: conversion to Catholicism, the act of writing, the sound of typewriters, hallucinations, mental breakdown, betrayal. Obvious I suppose but then so much of fiction is based on the author’s personal experience albeit I take a contrarian approach: my memoir writing is a thinly disguised fiction.

Spark even references her battle with the Inland Revenue in 1952 (see here):

‘Change your evil life,’ said Georgina.

‘You don’t know what evil is,’ Mervyn said defensively, ‘nor the difference between right and wrong … confuse God with the Inland Revenue and God knows what.’

If only it were that straightforward. HMRC's civil investigation powers are frighteningly extensive.

First published on Linkedin